This article from Bonhams Magazine Website is retained here to ensure its longevity. All inquiries should be referred to Bonhams Magazine or the author Rupert Christiansen who published this article in the Spring 2005 edition of Bonhams Magazine. Rupert Christiansen is the arts columnist for the daily telegraph. Copyright is retained by the Cass Sculpture Foundation.

|

I'll do it my way

Article by Rupert Christiansen - Bonhams Magazine, Spring 2005

First published in the Spring 2005 edition of Bonhams Magazine |

is entirely privately funded. Rupert Christiansen meets

Wilfred Cass, the man behind this ground-breaking venture

Rolling over a West Sussex hillside, deep within the Goodwood estate a few miles north of Chichester, the Cass Sculpture Foundation extends across 26 wooded acres. Sixty-odd pieces are dotted among trees, lawns and ponds — some are monumentally grand, some austerely enigmatic, some smartly witty. Andy Goldsworthy has designed a sandstone arch that stretches like a rainbow over the estate's flint wall, built by French prisoners-of-war in 1790. Stephen Cox has perched ancient catamarans on rows of spindly granite pillars. At the end of a vista, Lynn Chadwick’s last work, an austere stainless-steel mobile, revolves in the wind. Tim Morgan’s Cypher is a huge translucent drum made up of glass rods, while Steven Gregory’s bronze shows a grinning fish surrealistically riding a bicycle. Wandering around this enchanted garden gives you a unique survey of the variety and invention that enlivens 21st century British sculpture.

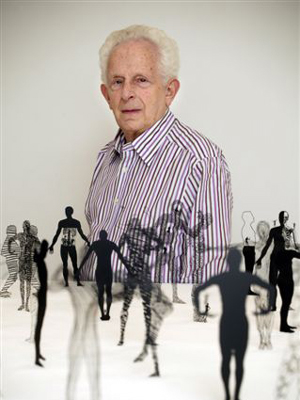

It’s the creation of Wilfred Cass, a spry 80-year-old with a distinguished career in electronic engineering and management, who moved here with his elegant wife, Jeannette, in 1989, just after the devastations of the hurricane. The couple had a small personal collection — Henry Moore had been a friend — but the idea of reviving what had been a commercial forest by landscaping it as a sculpture park only came to them after they abandoned an initial plan for an open-air theatre. Nothing if not thorough, the Casses then spent a preliminary year visiting parks in Europe, North America and Japan, returning to Goodwood with a suitcase full of ideas, as well as bags of scepticism.

“We were inspired by Storm King in upstate New York, but many of the schemes we saw were too large, both in acreage and the amount of sculpture they contained,” Wilfred Cass recalls. “There was a lack of aesthetic focus, and the display of a permanent collection was often restrictive. There wasn't enough emphasis on quality. We thought we could do better.”

And so they have. The Cass Sculpture Foundation, established in 1994, is relatively small and exclusively devoted to modern British artists. Nor is it in any sense a museum, as almost all pieces are commissioned and then displayed for only three or four years, during which time they are up for sale. The underlying principle is not commercial, but it is entrepreneurial — the Foundation pays the sculptors’ costs, which it recovers when the pieces are sold, ploughing the proceeds back into further commissions.

It takes no Arts Council or public subsidy, nor does it solicit any — Cass is adamant that he can do the job better without interference masking as financial help. “All the administration is done on a couple of Macs in a paperless office. We run a tight ship and can act fast, because we don't get policy imposed on us from elsewhere. Committees just slow you down and land you in avoidable messes, like the Diana Fountain in Kensington Gardens. Because we're not accountable to anyone else, we can turn on a penny.” Well, slightly more than a penny — to date Cass’ personal investment totals about £6m, with the annual figure now standing at about £400,000, as the Foundation prepares for a significant expansion of its activities.

Cass hasn't always been so optimistic, he admits, and the park’s first three years were hard. “Our friends kept telling us that the park was a white elephant. We had a lot to learn. There were problems with the artists and their galleries — that’s an area which can still be difficult. But we persevered and got things right, and now we're ready to move on.”

In 2004, the Foundation opened a London showroom in Percy Street, off Tottenham Court Road. This serves both as an information centre and a gallery, which sells maquettes and casts of the Goodwood exhibits. This year sees the inauguration of a new-four-acre site inside the park — a converted chalk pit that will be used for one-man exhibitions, starting with the work of Tony Cragg, a sculptor Cass considers “without peer in his generation.” Now 55, Cragg has lived in Germany for nearly 30 years and, despite winning the Turner Prize in 1988, his work is probably more celebrated in mainland Europe than in Britain. But this is not a peak-of-career retrospective — in keeping with the Foundation’s forward vision, none of the works on show will be over a year old, and at least 12 will have been commissioned by Cass as ‘site-specific’ responses to the Goodwood landscape.

This won't be the end of expansion. Construction has also started on a new 500sq metre building in the grounds, designed by Craig Downie. This is scheduled to open in 2006, and will house the Foundation’s library, archive and research centre, as well as a gallery that can double as a seminar and conference space. “Some sculptors’ work just isn't suited to exposure to the elements,” Cass explains. “I think this indoor space is vital if we are to be truly representative of all the trends and styles in British sculptures.”

That so much has been achieved so quickly is largely due to the Foundation’s refusal to join the merry-go-round of the art establishment and ensnare itself in the tendrils of subsidy and fund-raising. There's a small board of advisory trustees, but staffing is minuscule. Tim Marlow was for several years ‘Creative Director’, but since he amicably transferred to the White Cube gallery and his successor proved short-lived, Cass has preferred to take all major decisions himself.

Nonetheless, he tries to keep his own predilections out of the commissioning process — this is not his collection, he emphasises, let alone an ego trip. Cass knows the scene well and takes the best advice. “But in the end,” he says, “it comes down to whether the artist can be creatively excited by the landscape of the park.” Twist his arm for personal favourites, however, and he confesses that Thomas Heatherwick — as much an architect, designer, inventor and engineer as he is a sculptor — clearly has a special appeal, not only because the Casses spotted his talent when he was 19-year-old student, but also because his polymathy echoes Cass’ own.

A German Jewish émigré whose family came to England in 1933, Cass is a scion of the distinguished Cassirer family, whose members include the famous art publisher Bruno Cassirer and the philosopher Ernest Cassirer. Recently, Cass was delighted to discover that a great-uncle “way back” had owned a sculpture park in Wilhelmine, in Germany, but his own father was a hard-nosed businessman who ran a paper-works and had “no interest in art whatsoever”. In 1942 Cass enlisted in the Royal Engineers, and after the war worked mostly in electronics, devising circuits for televisions. Later he had a huge success as a management consultant, sorting out companies as diverse as men's clothiers Moss Bros and art suppliers Reeves. Through his involvement with the latter, Cass came to know Henry Moore, who was interested in learning about watercolour, and it was this encounter that stimulated Cass' fascination with artistic creation.

The way that the Sculpture Foundation allows Cass to match this fascination with his business acumen and organisational skill gives him profound satisfaction. “I like finding solutions to problems and working out systems in which everything fits. The park is not just a dream — I attend to every detail, from the marketing and publicity to the concrete on which the sculptures are fixed.”

The market is small, Cass says. There are perhaps 500 individuals in the world who buy sculpture seriously, and many of the Foundation’s sales are made to commercial institutions and public authorities. Newcastle’s buying policy has been very enlightened, he adds, and he also praises the London Borough of Woolwich and the residential developers St James’ Homes.

What the Foundation needs now is a change in the tax laws that would favour donors to artistic and charitable causes. “If I had five minutes with the Chancellor, that’s the case I'd put. The sense of it is glaringly obvious: it would cost practically nothing and it would release a lot money. But he won't do anything that smells of favouring the middle classes, and that is sadly holding a lot of good things back.”

Rupert Christiansen is the arts columnist for The Daily Telegraph.

All contents © copyright 1992-2005 Cass Sculpture Foundation. All rights reserved.