| Cassirer |  |

Boom in the Founder Years: From Schwientochlowitz to Breslau

The Cassirer family has a long and extraordinary history. There are sources from which it can be pieced together including books written by members of the family, the archives held by Yale University, the Geheeb archives, recollections by members of the family caught in interviews, the genealogical work that has been done by Michael Geballe, Niels Waller, and others, documents handed down in the family, and the living memories of Cassirer descendants (brought together now, twice,first in a reunion in Berlin in 2002. and ten years later in a a reunion in London in 2012). Progressively it is hoped to bring more of this material together here. What follows is an account highlighting the material already collected here.

The early history of the Cassirer ancestors has already been sketched (see here). The modern history, as described by Werner Falk, begins with Markus Cassirer and Jeanette Steinitz, in Upper Silesia, in what is now Poland, in a place called Schwientochlowitz in or about the 1860's. (Schwientochlowitz was a small village with a population of 14,612 in 1905). Markus Cassirer and Jeanette are shown as being cloth merchants and makers of looms.

|

|

|

Markus Cassirer (1801-1880) and his wife Jeanette.

(From the Family Trust document, 1890)

Markus and Jeanette Cassirer had seven sons (Louis, Julius, Eduard, Salo, Moritz, Max, and Isidor) and two daughters (Rosalie and Julie). The sons all moved away from the country as they grew up and moved to Breslau which was a big and rapidly growing city of Germany - with a strong history of economic, cultural and intellectual achievements.

Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland)

One family recollection is that Markus and Jeanette Cassirer had a country pub where they made a slivowitz. (a type of plum brandy) according to their own recipe as part of their business. That story may mix up Markus with Siegfried Cassirer (Markus's brother) who is shown as having been a Brewer.† Alternatively, and equally credibly, both brothers in one way or another shared skill in and adopted the brewer's craft.

|

|

|

Another brewer

Siegfried Cassirer (1812-1897) and his wife Henriette .

(From the Family Trust document, 1890)

Siegfried and Markus would eventually be connected together in a Family Trust (established in1890). But they were not the only brothers. There was also one who was in the timber industry and lived in Breslau. This"Breslau uncle" was very interested in the sons and, as they came from Swientochlowitz to Breslau, he would find jobs for them in the timber trade. Only one of them was sent to university.

Three of the Cassirer brothers, from left Max, Isidor and Salo Cassirer |

Salomon (Salo) Cassirer in earlier days |

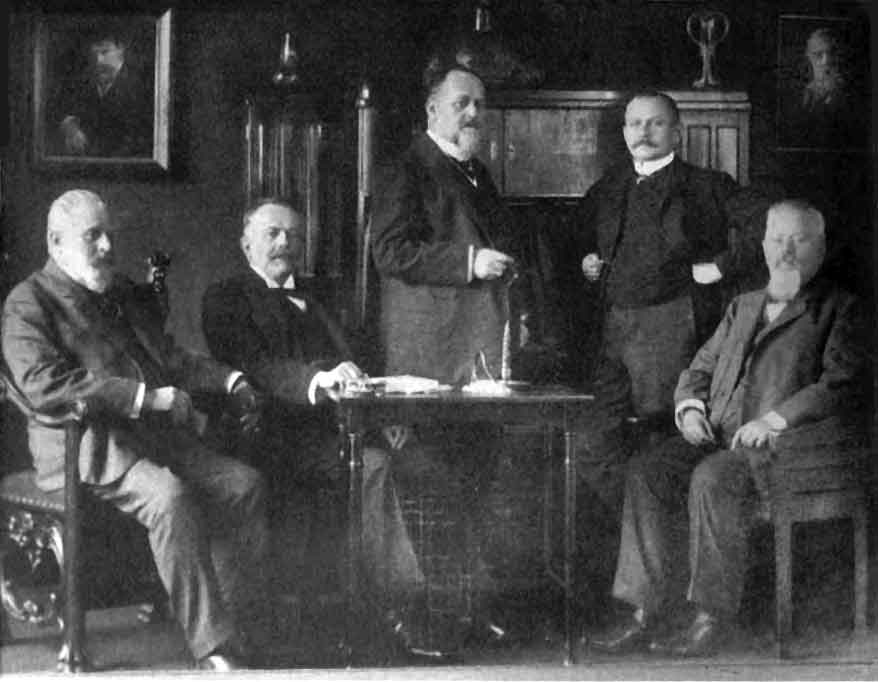

Five of the Cassirer brothers (from left): Julius, Eduard, Louis, Max, and Isidor Cassirer, circa 1900

[Date: before 1904, photograph source: Neils Waller, identification of brothers by Claude Cassirer]

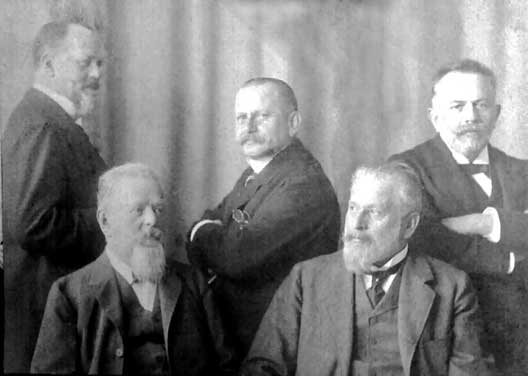

Earlier photo of five of the Cassirer brothers (from left): Louis, Isidor, Max, Julius, Eduard

[Photograph source: Claude Cassirer; identifications written on back of photograph]

This was the time directly after the war with France and the unification of the Reich and a time of tremendous economic boom, which they called the "Gründerjahre" - "the Founder's years". Being in the timber trade was very profitable because there was a lot of building going on, especially in Berlin.

For the Cassirer brothers a move to Berlin promised great opportunity. Available evidence suggests the Cassirers began their commercial activities in Berlin in the vicinity of the Warsaw Road (whose southern end, up to 1886, formed the eastern boundary of urban Berlin). According to historian Wanja Abramowski, near the southern end- close to what is now Warsaw Place - stood a water company, and all around were the timber yards of the brothers Cassirer. There was a constant stream of immigrants creating demand for accommodation, providing labour for increasing numbers of new enterprises, with consequent investment and rising property prices. Between 1887 and 1889 the first dwelling houses developed there, while the land development at the northern end began in 1896. Julius Cassirer was centrally involved in this development. And so the brothers also started to speculate in building and they built big apartment houses in Berlin.

One part of the Warsaw Road (Warschauer Strasse) in 1908

Isidor Cassirer, one of these seven sons, was typical of them. He went into the timber trade and made some money, and then moved to Berlin from Breslau in the 1870's.

|

Isidor Cassirer |

Second wife Lydia (ne Kopelanski) |

Isidor then had the bright idea together with the brother who had been at university to move into the manufacture of pulp and the even more brilliant idea of starting this pulp factory where the timber was - in Poland. So they created a big pulp factory in Bratislava And this made him a millionaire.

When the 1914 War came there was great anxiety whether this factory in Poland would survive. Would there be fighting? As it happened the fighting never really came across that part of Poland and when the War ended the factory was in as good condition as ever. But Germany were on the losing side. The law of the new Poland provided that Germans could not own property in Poland. So Isidor and his brother had to sell the factory. They sold it for 11 million marks to an American consortium. This was paid across in Switzerland in Swiss currency - a very nice result.

|

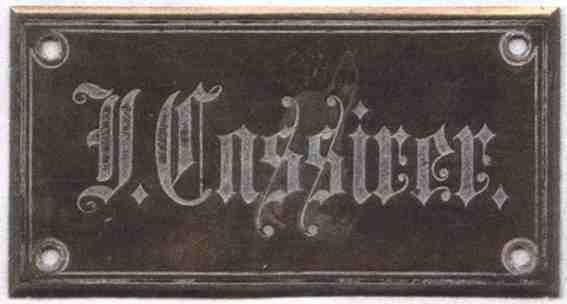

Name plate from the office door of Isidor Cassirer |

Much the same happened to almost all the other brothers. The brother with whom Isidor had started the factory in Poland also had already started with another brother a factory in Czechoslovakia.

Family accounts recall only one of the brothers - Moritz Cassirer - who did not show much interest in the business affairs of the family and rather, as it is remembered, was more interested in playing cards. So the family decided to give him a sum of money to start out with and sent him off to America in the hope that he would make something of himself in the new country. (There, he settled in New York where he remained proud of his family background and German origins: For more on the story of Moritz and his descendants, click here.)

Eventually all the other brothers had factories and other ventures and, as time went on, a good deal of money. They would never borrow. They met, all of them, every day, at 4 o'clock or so in a cafe in Berlin and there they exchanged views on their businesses and made arrangements about how to finance each other in what was effectively a family trust.

Isidor was well known in the family for being technologically very interested. He was one of the first people in Berlin to have a telephone and Betty Cassirer would later recall that he would tease his friends and customers. Because when they came to the entrance of the business (when he still had the timber business) - it was a big area that their timber business covered - and they had to mention their business and their name and they would let them in, and when they arrived at Isidor's office he already knew who was coming. And people would say "how does he know".

With wealth comes also the possibility to make a civic contribution. Max Cassirer was particularly notable in this regard.

Max Cassirer |

At the Odenwaldschule with his granddaughter |

Max Cassirer devoted his" leisures" to the municipal businesses of Berlin, and his wealth to help his daughter Edith Cassirer and son-in-law, Paul Geheeb, to create the Odenwaldschule - a very progressive school which, as his grandson Heinrich (Henry) Cassirer would recently describe, was intended to become "the cocoon of a humanistic education". Much has been written about the Odenwaldschule, how it managed to survive in Nazi Germany for a time. One account of the experience of the Odenwaldschule in 1922 is offered by Klaus Mann, the well-known playwright and author (and son of Nobel Prize for literature winner, Thomas Mann).

Max Cassirer was a member of the Democratic Party and became a notable city council man in Berlin Charlottenburg.

The sons and daughters made one large extended family which met, argued, teased and dined regularly. All were doing interesting things and the wives and children formed a constant and complex social network. Yet, of course, the reality was not so tranquil. There was after all the strong but humorous Cassirer personality in full play. One gets a sense of it from the letter below, by granddaughter Marie Charlotte Loewenberg, in the newspaper published on the occasion of the golden anniversary of Julius and Julie Cassirer on 17 March 1918:

Letter from MARIECHEN LOWENBERG to her friend Lotte

How we spend our Sundays:

Dear Lotte,

Sundays were spend mostly with our dear grandparents. My father says, he’d rather stay home, he can’t really sleep at the villa, there aren’t enough sofas, but we still have to go. Around half-past three everyone has gathered; usually one of the children is missing due to a cold or such. Uncle Bruno is usually late. Everyone yells at him, but he stays calm and silently reaches for the paper. Now we go to the dining room. Aunt Else is called to the phone. Mutti serves the soup. Father always wants two bowls, grandfather tells him not to be so greedy, we’re not in Pomerania. Then comes the roast. It’s usually hen; Father says he’s sick of it already. Grandfather is always served last. Grandmother says he can wait, the guests come first. Aunt Else is called to the phone. There’s always compote, 4 kinds, they taste great. Grandfather says, “I’ve already forbidden you a hundred times to put so much Kompott on the table, what will we do with it all”. Grandmother says, he should mind his own business, as it has nothing to do with him. The others say almost nothing. Fritz and Robert kick each other under the table. Aunt Else whispers about the Liebermanns and so on with Uncle Bruno. Now comes dessert, always warm, there used to be such lovely ices, which we much preferred, but that’s all confiscated now. Fritz eats two helpings. Grandmother urges him to a third. Grandfather says, “The kid will explode now”. Grandmother says, “Just let him eat, the boy looks so miserable”. Father is called to the phone, a patient needs to talk to him. He’s very angry: Not even on Sundays will that gang leave him in peace. Now everyone gets up. Grandfather is very tired. Grandmother says, “It’s not polite to go sleep when one has company”. But Grandfather goes anyway. The other guests’ heads are nodding, too, by now: they lean on each other. Father takes his coat off. Mother says, “That’s ugly!” Father takes his tie off as well and lies down. Grandmother stays lively and asks me, “Well, Miekchen, and what are you up to?” I say “I’ll go for a walk with my Anni, it’s too boring here for me!”

And I go. Dear Lotte! I must close for today, as I must still practice for the Golden Anniversary. More next time.

Your, Mariechen

This of course was the weekly Sunday extended family dinner. Many more such amusing anecdotes from daily life of the extended Cassirer family can be found in the booklet produced for Max Cassirer's eightieth birday [for the English translation click here]. And there were also the grand formal events such as the one shown below in December 1920 on the occasion of the marriage of Isidor Cassirer's son Rudolph to Eli Ruth.

[Centre facing at table: father Isidor Cassirer, bride Eli Ruth (in marriage dress), groom Rudolph Cassirer, and mother Lydia]

So domestic, social and business life developed into a rich dynamic picture. As a whole the seven sons and two daughters of Markus and Jeanette Cassirer had been very successful. But not only were they successes but, with this background, so were their children, many of whom, as will be described, became very prominent. However, as the family of Isidor sat around the celebratory dinner table in 1920, it is unlikely they could have begun to understand how dramatically this nice picture of success would, in another 18 years, be disrupted by the advent of the Nazis.

|

|

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

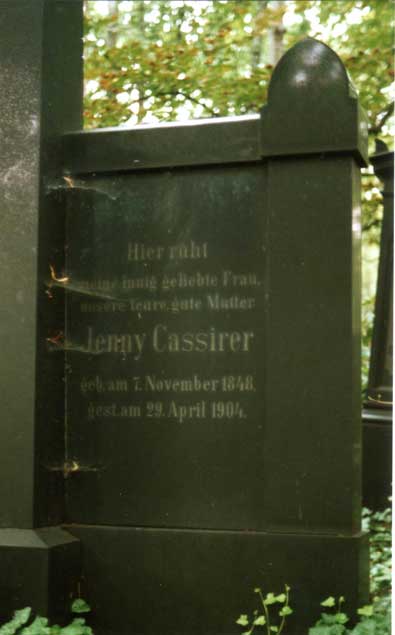

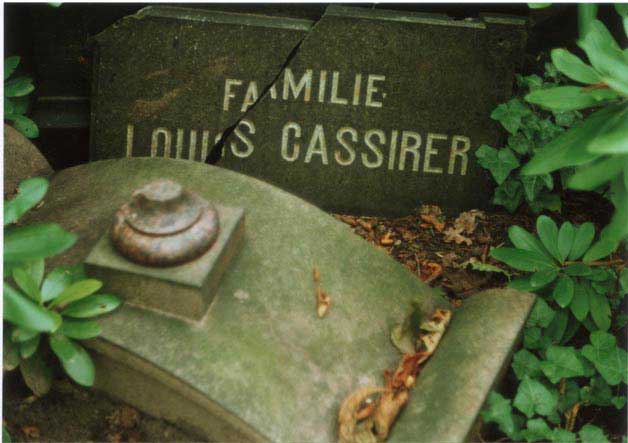

| Grave: Isidor and Else Cassirer | Grave: Eduard and Jenny Cassirer | Grave: Louis and Emilie Cassirer (all in Berlin) |

Back to Contents / Next page: The Breslau Generation

Click here for Cassirers: Breslau to Berlin; Music, Publishing and Art; Continuing the Entrepeneurship; Daughters; The Scattered Generations

To see some genealogical sites which have supported this one by listing this in their directories click here