The Cassirers, whilst of Jewish lineage were not religious. As Werner Falk said:

They were not Jews who tried to conceal that they were Jews. But there were members of the family people who got baptized, people who became outspoken German nationalists - all that sort of thing. The common attitude in the family was illustrated by that of Isidor. You could never see him near a Synagogue. He thought the Synagogue was something for women. My grandmother - his wife - could go there but not him.

As with many other Jews of their time the Cassirers also identified as patriotic Germans. This was not just a self-perception. Elsewhere on this site is displayed a telegram to Lydia Cassirer from Field Marshal Von Hindenburg thanking her for her contribution to Germany's First World War effort. Isidor's grandson, Ernest Cassirer writes:

My grandmother's commendations were for having opened up the Cassirer villa for use by German soldiers in need of rehabilitational treatment after war related amputations. I have many newspaper articles with pictures of this activity. Also pictures of my grandmother with the Kaiser.

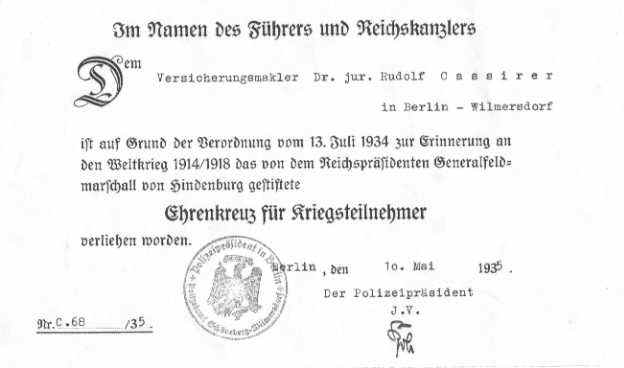

In retrospect, perhaps the greatest irony was the Certificate dated 10 May 1935 attesting to the presentation of the Cross of Honour to Isidor Cassirer's son, Dr. Rudolph Cassirer, in the name of Führer and Reichs Chancellor, Adolph Hitler.

Rudoph Cassirer

At the time this represented the still constrained power of Hitler, which remained subject to the decree by Reichs President, von Hindenburg, that the award be made to all veterans of active service in the German army. Hitler complied and it was sent to all veterans - Jew and Gentile alike. That did not inhibit Hitler from escalating the systematic murder of all Jews in the following years.

Despite their patriotic self-perception the Cassirer Breslau generation found that they were Jewish enough to become targets of anti-Semitism. Werner Falk talked of his experiences as an older school child:

And then we went back to Berlin and there was the 1919 revolution and all the anxiety connected with that. I mean we had shooting in the street and went to school past a big hotel which had been turned into a fortress. So it wasn't a very peaceful early days.

And then one consequence of this was that I never managed to get into the right school. I mean, what do I mean by the right school? There were two gymnasia where young people of our class and religion would go. They were academically famous and if you had been to any of them you would have been with your likes. But I had to go because I couldn't get into these - it was all too late - I had to go to school which was the opposite of this. It was in a very reactionary Berlin district where there were no Jews but only reactionaries. It was stupid. The teachers were reactionaries and anti-Semites and the students, these boys, also. I mean we got the full brunt of anti-Semitism there and I remember I was a big strong 12 year old [in 1918] and I remember in the lunch break the few Jewish guys that were there in that school would line up behind me in a corner of the courtyard and the college students would attack us and we would defend ourselves. It wasn't pleasant at all.

The progressive Odenwaldschule, founded by Max Cassirer, was similarly confronted by the rising tide of anti-semitism. Although it managed to operate with the Nazis in power for a time, in 1933 a group of SA men stormed the school, flogged Max Cassirer's son, Kurt Cassirer, collected "Jewish and communist literature" and burned the books in Goethe place, the central square of the school. As mentioned earlier, following that, in 1934, the School was forced to move to Switzerland where it now continues to operate.

Enough has already been said to indicate the profound impact of the anti-Semitism. Later there was its steady rise with the assistance of the Nazis, and its progressive transformation into every more fearful action. Henry Cassirer writes that "Sitting in her deck chair on the balcony of Platonhaus, my mother answered her brother in a letter dated March 5, 1933, day of the election: My dear Fritz, also I feel like a madness, a horror, a cheating, a true dirtiness, the recent event which is a negation of all that I like and of why I live ." The impact of this ever worsening condition upon the Cassirers and their families and relatives was also progressively more severe. Ultimately it began to emerge as a choice of leave or die. Some left early and some with greater difficulty much later.

One who left his departure very late was Max Cassirer. Professor Peter Paret notes that Max did not believe that national socialism was more than a passing phenomenon. In 1933 Professor Paret's mother, Suzanne Aimee Cassirer wrote to Max urging him to leave Germany. Professor Paret has the letter in which Max replied that she was too emotional and that he could judge the situation for what it was. Max was of course terribly wrong. But nevertheless he was able to emigrate at the last moment, first to his daughter in Switzerland, then to his son.

Regretably there were some who did not leave in time and were killed by the Nazis.

Toni Cassirer aged 52, the daughter of Eduard, and her husband Dr. David Koenigsberger aged 75 (despite being twice awarded the Iron Cross - First and Second Class), were transported from Berlin on 11 September 1942 on transport I/64 to their deaths at Theresienstadt concentration camp. There is a record of David's death there on 30 October 1942. Toni Cassirer is simply recorded as having died.

Lucie Lasker, the mother of Lisbet, Martin Cassirer's wife, at 72 years of age was too old to leave Germany in 1938 and stayed. Her great grandson, Ben Bano has a postcard from Lucie (to Georg Cassirer) which was kept by his mother. Lucie had probably arranged for the card to be posted when she was held in an interim holding camp at Riebnig (now Rybna, Poland) in March 1942. This "group housing" [Wohngemeinschaft] had been established by the Nazis, operating over October 1941 to March 1943, to temporarily hold Jews who had been transported from Breslau, before sending them on East to the concentration camps. (For Ben Bano's account of Reibnig click here.) On 31 August 1942 Lucie was sent on Transport IX/2 to Theresienstadt concentration camp where she is recorded as having died.† (Although Theresienstadt was not equipped with a gas chamber most prisoners there were doomed to die from the starvation diet and other appalling conditions or else were transported on to Auschwitz or other death camps. Of the arrivals at Theresienstadt only one in eight ultimately survived.)

There are two messages on the postcard, each probably shaped to evade censorship. The first, from a friend, Willy, seems framed to convey the news that his sister Grete has died, five weeks earlier. (Willy was clearly a good friend of Georg's wife Vera, and, although the signature is hard to read, has now been confirmed as being Willy Bodlaender - for more on Willy Bodlaender and his family click here.) Lucie's message on the postcard is shown below. Having mentioned how her grandson Erich used regularly to write to her it concludes, with probably studied ambiguity: 'Now it's all at an end. Heartfelt greetings, and you think of me.'

The tragedy for Lucie does not end with this card. The Auschwitz Death Register shows that Lucie's son Hermann also died at that death camp on 18 Feb 1943.

Two others, who were killed in the death camps, were Fritz Siegfried Loewenberg son of Elise Cassirer and his wife Marion. As with quite a number of other German Jews, Fritz and Marion sought refuge in the Netherlands. In February 1941 there is a record of them living at De Lairessestraat 147 huis, Amsterdam. However, on or shortly after that date they were deported to Auschwitz. Marion (recorded as Maria in the Dutch records) died there on 7 Sept 1942. Fritz was declared dead and a victim of the Holocaust at the end of the war.

Hannah, sister of Lilly Cassirer is also known to have been killed in the death camps. (There is a record which suggests, not yet conclusively, that she died at Auschwitz.) Another was Ludwig Katzenellenbogen, the man that actress Tilla Durieux married after she divorced Paul Cassirer. He escaped with Tilla to Yugoslavia and started a hotel in Abbazia. There he was arrested in 1942 when the Germans entered and he died in Oranienburg Concentration Camp in 1944. (Tilla joined the Yugoslavian partisans.)

Julie Cassirer's daughter Edith married John Waller. His mother Regina, born on 29 Aug 1861, was deported on 24 Sep 1942 (at the age of 81) from Vienna to the Theresienstadt Concentration Camp and died there on 2 May 1944.

The daughter of Grete Cassirer and Arthur Mayer - Lucie Beate Mayer, Lucie's husband Heinrich Gabel, and their son Gerhard were part of the group of the fateful journey of the St Louis in 1939. This ship from Germany was on a special trip carrying almost entirely Jewish refugees. It went first to Cuba, where almost all were denied permission to land, then to the US where it also was refused permission to land, and then turned back to Europe where several countries (including France and the Netherlands) gave them temporary safe haven. Tragically those countries also fell to the Nazis and the refugees were arrested and transported to the death camps. Lucie, Heinrich and Gerhard were amongst those who went to the Netherlands. The US Holocaust Museum study of the fate of these passengers reports:

Among the passengers who went to the Netherlands, Beate and Heinrich Gabel were deported from the Westerbork transit camp to the Theresienstadt ghetto with their son Gerhard. They subsequently were deported from Theresienstadt to Auschwitz in October 1944. Gerhard was seven years old at that time. Heinrich was sent on to Golleschau, a subcamp of Auschwitz, where his name is listed in the records of the prisoners hospital on a document dated October 28, 1944. He died on February 28, 1945. There is no record that Beate or Gerhard survived.

Sadly, what the above understated final sentence omits to say is that, in all probability, Lucy Beate and Gerhard were murdered upon arrival. As already mentioned there was little effort made to keep track of those were selected as unsuitable for work, or who refused to be separated from children who had been selected, and consequently were sent straight to the gas chambers.

Walter Bruno Kaufmann, the father of Marion Cassirer (wife of Ernest Cassirer), was also murdered at Auschwitz on 13 Jan 1943. Marion herself only survived through the heroic acts of a number of people who provided her with protection at great risk to themselves.

|

Marion Kaufmann - later Marion Cassirer - (centre) aged 8, in hiding under the shelter of a Gypsy family in the Netherlands in 1944 |

For a more comprehensive account of Marion Cassirer's extraordinary story of survival as a hidden child click here.

A list of twenty-five known victims of the Holocaust from the family tree which is the subject of this site may be seen by clicking here.

Whilst death was the direct outcome of the holocaust for a small number of the Cassirers, most managed one way or another to make their move early enough, to leave Germany before doing so became impossible.

Each story is no doubt unique. That of Werner Falk, the son of Betty Falk (ne Cassirer) is just one example [adapted from Werner's third wife, Jeanette Falk's chapter, and an earlier interview with Werner before he died.]

Werner went to the University of Berlin, then transferred to Heidelberg where he finished a Ph.D. in Political Economy in 1932. He obtained a teaching position at the Hochschule für Politik, the youngest, he was told, ever to hold such a post. But by then, Germany was becoming inhospitable for a liberal/socialist Jewish intellectual. Packing for a ski trip in Austria, he threw in a suit along with his usual gear. During the holiday, at Obergurgl (a very fine ski resort at 3,500 metres - where Hitler eventually constructed a resort for his officers, now used as the Austrian Ski Academy).

As Werner put it: "After two weeks, I opened the paper and there was the Reichstag's fire. And from there on there was no peace. this telegram from my parents saying that I should stay and ski more and more because it was necessary for my health. And - well it was all quite clear because our Institute was the first thing which was taken over by Goebels. Because that was to turn it immediately into a political propaganda institute. And so finally I did not come back to Germany but went to Switzerland where we had friends.

"Oh then I went to France. Then we all played a crazy game. I mean, between Zurich and Paris, and Paris and Zurich. Where would we go? And then I decided there was no future in either Switzerland or France for various reasons, and the head of the School of Politics had in the meanwhile for the moment gone to London. And I was in correspondence with him and he said come here. Come to London. I will find you something. And I got something there - a kind of scholarship. English Jews collected money for a fund to support refugee scholars before they could really be settled. And I got some of those funds and stayed in England."

Werner never returned to live in Germany. Determined to pursue his career, he found that the English university system had no use for a German Ph.D. He had to go through the undergraduate program and, what is more, he would need to emerge with a "First Class Honours" degree: the British equivalent of summa cum laude. He began an intense effort to master his new culture. He read English literature, 18th century philosophy and anything else that came his way. The "First" at Oxford was duly won and he was taken on as a lecturer at New College in 1938.

Werner stayed at Oxford until 1950 when he departed with his wife and three children for Australia, where he took up a position in the Philosophy Department at the University of Melbourne.

Other's of the Breslau generation and their children found their way to other countries - Scandinavia, South Africa, the UK, and the USA. Barbara Falk, Werner Falk's first wife, who he met in Oxford and who supported him through this period, has written about the difficulties that those Jewish refugees with academic qualifications faced. A number of them, including Werner, Ernst Cassirer, Heinz Cassirer, and others found their way to Oxford under a refugee scheme. There they faced what was an unfamiliar and strangely different intellectual and cultural environment in which they tried to once more function as intellectuals.

Eventually, it may be possible to reproduce the relevant parts of this account here. But in summary, whether academic, entrepreneur, art connoisseur, engineer, or child, the task of fitting into deeply foreign environments ,with profoundly different modes of thinking, customs and language, not themselves always devoid of anti-Semitism, and generally at war with the country from which they had come, was deeply confronting and disorienting.

It would be good to assemble more of the character of these multiple experiences, and perhaps these may exist and be able to be brought together here. Certainly the invitation is open to send anything that would add depth to this. But given the extraordinary disruption presented by these experiences, it is remarkable how well the Cassirer families fared in putting together new lives, in the far-flung communities in which they found themselves.

Even if it were known it would be impossible to present here the diverse outcomes for each of the dispossessed Breslau generation and their children as they made their way forward in their scattered locations. Here description is confined to a few of the members of the family who arrived at different destinations, their diverse reactions, and the range of approaches that they took to make their way forward attempting, sometimes (but not always) with great success, to put together shattered lives on the basis of what they had remaining - their talents and some possessions.

Oxford:

Heinz Cassirer

(1903-1979) Arriving in the United Kingdom,

Heinz could not speak English . Nevertheless, within a year he

was lecturing in Philosophy at Glasgow University. Not long after

he moved to Oxford where he began to lecture at Corpus Christi

College.

Heinz Cassirer - Grace Luckin |

An Oxford Don, Donald M. Mackinnon, gives the following account:

Dr. Heinz Cassirer, the son of Professor Ernst Cassirer came to Oxford from Glasgow where as a protege to Professor H.J. Paton, who had been professor of logic and metaphysics there before returning to Oxford as White's Professor of Moral Philosophy in 1937, he had written in English a commentary on Kant's Critique of Judgment.

Cassirer had lived under the shadow of his very distinguished father in Germany before the Nazis came to power, and felt the need to define his identity not only in the alien world of Oxford, but in relation to Ernst. This though he shared his father's great regard for Kant's philosophy, on which he often lectured, summarising in Kant's First Critique (1955) his own views of Kant's relation to the then widely prevailing empiricism. (This book however appeared after Heinz Cassirer had returned to a lectureship in Glasgow.)

A gifted man, more continually aware of the horrors he had left behind him in Germany than many realised, Cassirer also achieved... a remarkable translation of Kant's Critique of Practical Reason, which he later revised, and which many hope may still be published. No one who had the good fortune to know her will ever forget the grace of Cassirer's first wife, and the hospitality she offered in the confined environment of their Oxford Home. Aware that there was not likely to be a permanent appointment for him in Oxford, in 1946 Cassirer sought and obtained the position in Glasgow which he occupied until retirement.

This formal obituary article gives an idea of the intellectual power of Heinz. And although he would have been considered eccentric (he was said at time to carry his dachshund dogs around in his briefcase) this was not necessarily of much note in Oxford. [It is recounted that Donald Mackinnon, the author of the above obituary was known on a sunny day to tutor by poking his head out one window, whilst his students were required to poke their heads out an adjacent window if they wished to hear what he had to say. Also, it is recounted that once he was lying as usual with his head under his study table when the Bishop of Oxford made a remark of which he disapproved. At that moment his head is said to have poked tortoise like from under the table cloth and bit the Bishop on his gaitered leg.]

The book by Heinz shown above has recently been published, some ten years after his death in which he has given his translation of the New Testament. He apparently spent 21 years studying the New Testament and then only 13 months translating it into English putting his command of foreign languages to good use. Cassirer translated direct from original manuscripts and was able to give a faithful rendering of the Greek texts. His own Jewish heritage and knowledge of Jewish customs is said to have given a unique insight into familiar Bible texts.

New York: Claude Cassirer (1921 - )

Claude and his father Friedrich ("Fritz" or "Fred") Cassirer left Berlin in 1933 when Claude was 12 and went to Paris.

Then Werner Falk went to Paris and brought Claude back to Oxford where he lived with Barbara and Werner. They assisted him to get entry into a public school - Dauntseys School in England. He spent his holidays with Werner and Barbara and Barbara remembers him as a very nice boy. He matriculated at the beginning of 1939 and went to France that summer to visit his father. It was there that war broke out (at the beginning of September) and despite efforts from Werner and Barbara he was considered an "enemy alien" by the British and not allowed to re-enter England. This was a crushing blow for him, as he had hoped to go to university. He never did get to university but spent eight years trying to escape Hitler. Traveling

with a German passport marked with a J for Jew, he was interned

as an enemy alien but managed to get to Morocco, where he survived

typhoid fever and then somehow arranged to travel on a boat to

New York City where he arrived in August 1941. There he worked as a photographer.

Beverly and Claude Cassirer, circa 2003

Claude met his wife Beverly in December 1942 when traveling on a night coach to New York where she had been invited to attend a Christmas weekend at West Point with a friend. They had seats next to each other. Beverly came from a Jewish religious and observant American family (of modest economic means) of Russian background. She started the conversation. She had been devastated by what she had heard of the news from Germany regarding what was happening to Jews, and Claude had been there. They talked through the night, and the romance started. Said Beverly, more than 60 years of marriage later, the romance continues! Claude became a sought after photographer in Cleverland, and Beverly attained her dream of going to university and achieving a BA Magna Cum Laude. Claude, who was working, audited classes. They now reside in San Diego. They have two children, David and Ava.

Left to right: Claude and Beverly, David, Fritz and Ava Cassirer, David (Werner) Falk and Betty Falk (ne Cassirer) in 1967.

At the age of 83 (as of 2004), Claude and his family were involved in a struggle with the Spanish Government, to return a painting original by Camille Pissarro in 1897, and acquired by his Great Grandfather, Julius Cassirer from Durand-Ruel, Pissarro's Paris dealer, only a few months after it was painted.

"Rue St.-Honoré, Après-Midi, Effet de Pluie" oil on canvas © 1897, Camille Pissarro.

This painting was inherited by Julius's son Fritz Friedrich-Leopold Cassirer , and when he died in 1926 passed to his widow, Lily Cassirer Neubauer (ne Dispecker). Claude, still a baby when his mother died in the influenza epidemic that ravaged postwar Europe, spent much of his childhood with his grandmother, Lilly, and remembers the picture well.

This account of the provenance of the picture is definitively established from a photograph, still in existence, of the picture hanging over the sofa in Lilly's parlor in Munich before the war. A copy of this photograph is shown below. A small Barlach sculpture of a peasant woman in a shawl, about a foot tall, is just visible on a table in the next room. This sculpture is now in Claude Cassirer's collection in San Diego, along with the beautiful carved china cabinet, which still contains Lilly's Nymphenberg china. Claude's son, David Cassirer, remembers that he and his sister used to take the dishes out when his folks were away and play inside the cabinet, taking turns locking each other inside - something not viewed so well by their parents! The Max Liebermann painting, hanging over the china cabinet, is still missing, lost in the war.

Lilly Cassirer Neubauer's lounge room in Munich, just before the war, with the Pissarro painting on wall over sofa.

(for computer enhanced close-up of picture on wall click here)

Claude Cassirer has petitioned the Spanish Government for the return of the painting. It is considered by experts to be a great exemplar of not only the work of Pissarro, but the Impressionists generally, and their view of Paris following its reconstruction by Napoleon II. The painting is considered likely to bring at least $20 million USD if sold at auction in 2004 and probably well above that figure.†

According to one account, Spain managed to maintain its territory free from World War II, which devastated most of the rest of Europe. Spain, with a small Jewish community, was not, therefore, a place where massive plundering of Jewish property took place. Nonetheless, its strategic situation between Europe, Northern Africa and America and its close political relationship with Nazi Germany and Italy made Spain a suitable environment for the individuals and organizations responsible for the plundering of Jewish-owned art. Their warehouses and logistics were frequently based in Spain.

Many accounts of Claude's search for the return of this painting can be found on the world wide web. The following ["Spain Refusal re Cassirer Art", 7 January 2004] sums up the situation as of that date:

A human disaster followed the rise to power of the Nazis. Mrs. Lilly Cassirer, a widow by then, and her grandson Claude, had to flee Germany. Other members of her family, including her own sister Hanna, who could not escape, were killed by the Nazis in the death camps. A Nazi agent forced Mrs. Cassirer to surrender her Pissarro painting to him. Later on, the GESTAPO seized the painting and included it in an auction in Berlin in 1943. Although Mrs. Cassirer reported the plundering to U.S., German and international restitution authorities, the painting disappeared for decades. The anonymous purchaser of the painting at the 1943 Berlin auction later sold the painting, which was then sold periodically to other parties, who moved the painting from one continent to another, until it was acquired by Baron Heinz Heinrich Thyssen-Bornemisza for his collection, which was subsequently acquired by the Museum Foundation Collection Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. Visitors see it now on the walls of the Museum.

In 2001, the Commission for Art Recovery and Mr. Claude Cassirer, sole heir of Mrs. Lilly Cassirer, formally petitioned the Board of the Foundation and the Spanish Government, which controls the Board of the Foundation, to surrender the painting to its legitimate owner, Mr. Claude Cassirer. Since Spain had attended the 1998 Washington Conference and had agreed to the Washington Conference Principles, the Commission had expected the Spanish Government and the Foundation to honour its commitment under the Washington Conference Principles and return the painting. In addition, the Commission believes that Spanish law requires the Spanish Government to return the painting.

The Foundation has, unfortunately, refused to return the painting for reasons such as the statute of limitations, even though the Foundation does not dispute the fact that the painting had been owned by Lilly Cassirer before she was forced to surrender the painting.

The Spanish Government has also refused to take action to return the painting to its proper owner. Moreover, the Spanish Government has refused to meet with the Commission for Art Recovery or to discuss the return of the painting with the Commission for Art Recovery. The Spanish Government has taken the position that the Foundation is a "private" entity, that the painting is private property and not the property of the Spanish Government, and that any claim for the painting had to be filed with the Foundation or the Spanish Courts.

The Commission has not accepted the position of the Spanish Government because the Spanish Government (i) provided the funds to acquire the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, (ii) provided the building (and the funds to renovate the building) in Madrid to house the Museum and the Collection, (iii) provided that two-thirds of the Foundation's Board of Directors would be government appointees (with the Minister of Culture serving as the Chair of the Board) and (iv) provided that if for any reason the Foundation would be dissolved, the assets of the Foundation would pass to the Spanish Government.

The Commission for Art Recovery urges the Spanish Government to honour its commitments under the Washington Conference Principles and to return the painting to Mr. Cassirer. The Commission has prepared a "White Paper" on the Cassirer claim, which it delivered to the Spanish Ambassador to the United States in September 2002.

Claude died on 25 September 2011 without seeing his stolen property restored to him. Nevertheless Claude and Beverly's two children are continuing his struggle for the return of their plundered painting.

Given their experiences it is probably not all that surprising that so many of Claude's generation express values which are sensitive to oppression and injustice. Here is a report, in Literature of the Holocaust, in which Claude gave his comments about his attitudes.

I feel I have a message to give. I'm sensitive to anything that reminds me of Germany. When they had this no-knock law, for example, that was too close to Gestapo technique for me--or that certain books were to be banned, or sterilization of groups of people. I'd like people to think of such things carefully and see the frightening implications. I want to resist this feeling of hopelessness that people get. They think they can't change the course of history. That's not true. I think there are people who have the guts and courage to do things and we should help them. I don't think we can dare to take our liberties for granted.

Anything can happen here. When I saw the faces of the people in the South preventing the black people from going to certain schools and using German police dogs and fire hoses they looked no different than the Nazi storm troopers with their dogs fighting the Jews. People are people. The Germans are no worse than others. If the government becomes immoral and sanctions such things there is danger for everyone.

If there's any hope of survival for the Jews they must unite and stand for what they believe. They must not hide. I found that out when the Jews of Germany said they were not Jewish, and Goering said, "I'll decide who's Jewish."

I have confidence in this country. It is as good a democracy as one can find. That's why I was so disturbed when the Nixon thing happened. The other aspect that troubles me is the crime and violence. I abhor the aggressiveness. I don't watch cowboy movies, with people hitting and shooting one another. I see no sense in such things.

New York - a chance reunion: Claude Cassirer and Edith Bondy

Edith Bondy (a daughter of Julie Cassirer), her husband and her son Hans Waller were living in NY. Niels Waller , recounts that one day Hans went to a local deli for some lunch and noticed a man staring at him. The man had recently arrived in the US from Europe. Many glances, but no words were exchanged. The next day Hans returned to the deli accompanied by his mother Edith Bondi. The mystery man was again eating lunch at the deli. Although they had never met before Edith Bondi went up to the man and said "You must be a Cassirer - you have the Cassirer forehead." The man in question was Claude Cassirer. Later Hans found Claude his first job in the US.

The above was a most serendipitous meeting. But it was unusual. Even in the same place there was thus no guarantee the scattered relatives would ever meet again. And they were not just scattered across a city - they were scattered across the world.

Seattle: Ernest Cassirer (1930 - )

Ernest Cassirer's grandfather was Isidor Cassirer and (with his wife Lydia) had a son, Dr. Rudolph Walter Cassirer. born in Berlin in 1895. He achieved a Doctor of Jurisprudence and became a an Insurance Broker. He and his wife Johanna, (parents of Ernest and Miriam) came to New York on visitor's visas in May,1938. They subsequently traveled to Cuba and reentered the US as immigrants. As Ernest puts it, for Rudolph Cassirer, the transiton was difficult for him and his family: "This child of privilege,and privileged in his own right, became a warehouseman, a laundry truck (lorry) driver, a jitney driver, a regulatory enforcement officer for the Washington State Department of Transportation,and finally back into the insurance business as an insurance agent."

After Rudolph and Johanna had left for their visit to the US, Ernest's sister Miriam, 2 years old, was in the care of Catholic nuns in Berlin, whilst Ernest, only 8 years old, was in a Jewish boarding school in Caputh, near Potsdam. He attended that school until Kristallnacht, 9 November 1938. The school was destroyed, and the children walked to the train station, and took the train to Berlin. Once in Berlin, with remarkable resourcefulness for an eight year old, Ernest contacted his father's former governess who lived in Berlin,who in turn put him in touch with Dr. Loewenstein,an old family friend since his father's teen years. Dr. Loewenstein and Kurt Schlesinger, a Jewish attorney and friend of Ernest's father, with the help of some "helpful connections" obtained visas and boat tickets for Ernest and his sister and in December 1938 Ernest and his sister came to New York. Kurt Schlesinger and the family also made it out and settled in Portland Oregon.

Ernest Cassirer now lives in Seattle USA where he has broken what seemed to be almost a family requirement to become an academic: Ernest jokingly refers to himself as “academicus interruptus”. In fact, he started to attend the University of Washington, majoring in English and Journalism but then gave up a partial scholarship to move back with his father who was very ill. He then began work at The Boeing Company, going to Electronics school both outside of work,and at Boeing. Ernest notes that "there were numerous opportunities for advancement within the company, one just had to take advantage of them. During one 4 month period I attended classes full time at 'Boeing Tech', and was paid for going (with a career change and promotion to boot)."In this way Ernest became a Quality Assurance Specialist in Boeing Aerospace and Electronics - a role which, despite his modest self-description, would still seem to reflect the intellectual skills characteristic of the Cassirer family.

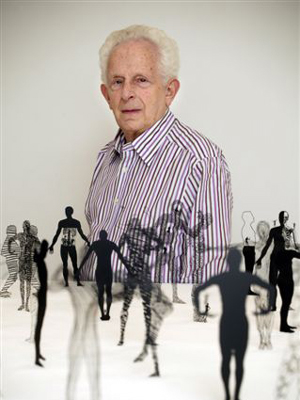

Ernest Wolfgang Cassirer

Ernest Cassirer's sister, Miriam, also still lives in Seattle. It was also in Seattle, USA where Ernest Cassirer's (and his ex-wife Marion's) son David and daughter Naomi were born. David works in California and at the time of writing (2004) was supervising a crew refurbishing and remodeling a number of public school buildings. Reverting more clearly to the academic Cassirer center of gravity, Ernest Cassirer’s daughter, Naomi received her Ph.D. at the Ohio State University in 1997,after a previous M.A. (also Ohio State), and a B.A from the University of Washington School of International Studies. Naomi has taught at the University of Notre Dame for a few years before joining the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Manila,where she now resides. And demonstrating another trend, perhaps in tacit reaction to the traumas experienced by their parents, there is a tendency in the next generation to focus on issues of injustice. Characteristically Naomi Cassirer is a gender specialist, traveling in various S.E. Asian countries as needed.

Paris: Henry Cassirer (1911-2004)

Born in Berlin, Germany, in 1911, Henry Cassirer attended the Odenwaldschule, the experimental school founded by his grandfather (Max Cassirer) near Frankfurt. With the rise of Nazism he left Germany for England where he completed his education and worked in radio at the BBC.

|

|||

Henry Cassirer - in 1941 at the BBC |

- with daughter and wife, c. 1975 |

- circa 2003 |

Henry Cassirer's book 2003 |

In 1942, Henry immigrated to the United States where he began a career with CBS and served as editor in chief for television news. After obtaining his U. S. citizenship he was employed by UNESCO and in 1952 moved to Paris becoming a roving ambassador and consultant for the organization.

Henry's papers from 1936-1996 are held at the University of Texas at Austin. Center for American History. They include: correspondence, printed material, scripts, notes, reports, audio tapes, photographs, speeches, and scrapbooks document the life and career of Henry R. Cassirer, particularly his work as a CBS executive in the 1940s and his long association with UNESCO. His works are prolific and include the following books:

Henry R. Cassirer, Und Alles Kam Anders

Henry R. Cassirer, Seeds in the Winds of Change

Henry R. Cassirer, Television Teaching Today

Henry R. Cassirer, Kommunikation und die Zukunft der Bildung

Reinhard Cassirer, B.A., The Irish Influence on the Liberal Movement in England 1798-1832, with Special Reference to the Period 1815-32.

Henry Cassirer's life to this point is nicely summed up in this review (translated from the French) of his new book, released in 2003, A Citizen of the 20th Century: Witness of the age(by Henry by Henry Cassirer, Honorary President and founder of the French Group of Disabled People):

Henry Cassirer has been witness to the forces of destruction and hope that have marked the 20th century and which he lives with determined commitment and openness to the world. Born in Berlin in 1911, his earliest memories recall the outbreak of the First World War. Raised in a spirit of democratic humanism in the Odenwaldschule, he faced the rise to power of National Socialism in resolute opposition, first in Germany and then as a student at the London School of Economics from where he undertook risky, secret missions to the Resistance in Berlin. On September 3rd, 1939, his resounding voice announced the British Declaration of war to the German people over the German-language service of the BBC.

In 1941, as assistant director of the CBS Short Wave Listening Station in New York, he collaborated with William L. Shirer to uncover German propaganda against the war, to draw it to the attention of President Roosevelt and reveal its echo in the American press. He was the first to report to the American public the invasion of the Soviet Union by the armed forces of National Socialism, as he recalls in a dramatic account.

Appointed by CBS as its television news editor, Cassirer established the first television news service in the United States. This book presents a vivid account of the halting beginnings of the TV medium. Cassirer obtained his US citizenship after lengthy legal efforts which were opposed by the FBI. Producer/writer of the first TV program on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights with Eleanor Roosevelt, he gained the attention of the United Nations.

In 1952 he was recruited by UNESCO in Paris as Director of educational Radio and Television. There he introduced innovative forms of community communication through Radio and Television in Europe, Asia and Africa. From a global perspective he wrote an early assessment of television as a potential tool of formal education.

Struck down by paralysis in 1956, following a mission to India, Cassirer was treated in England's Spinal Injuries Center at Stoke Mandeville. There he discovered the world of the disabled and their contribution to society. Inspired by FDR and his recognition that "the only thing to fear is fear itself", he later assumed leadership in France, and in the world wide movement, for equality and independent living of the disabled.

He returned to Unesco, with 'manageable' disability, and pursued his career as an international civil servant until his 'retirement' in 1971 in Annecy, Haute Savoie, at the foot of the French Alps. Here he has continued to once more apply his experience to the promotion of grassroots communication and the rights of the disabled.

Retracing his life experience and continued involvement, the book analyses the functions of democratic communication in our age and the role of a citizen of the world who is committed to meet the challenges of the modern age.

Henry Cassirer died on 29 December 2004 in Saint Jorioz, France. His funeral notice can be seen by clicking here. A web site has been created in memorium for Henry Cassiter which can be seen by clicking here.

Göteborg: Peter Cassirer (1933- )

Peter Cassirer was born in June 1933 in Berlin as the son of the pianist Vera (ne Chotzen) and Georg Cassirer. Georg was the son of Ernst Cassirer and in 1935 Ernst Cassirer was given a personal Chair at the University of Göteborg which he held to 1941. This made it possible for Georg, with his family, to emigrate to Sweden where Georg became a photographer. Georg's son Peter Cassirer and wife Ulla, still live in Göteborg. Peter's earlier career was as an opera singer, singing smaller tenor parts as Remendado, don Curzio and the circus director in The Bartered Bride (his favourite role).

Peter Cassirer (center) with grandfather Ernst Cassirer to left, and father Georg to right. Göteborg 1938. |

Peter Cassirer in his favourite operatic role as circus director in The Bartered Bride. |

Peter Cassirer with wife Ulla 2004

|

Peter was the first to re-introduce Rhetoric as a university subject in Sweden which he did at the Institute for Nordic Languages of Göteborg University. He taught there from 1970 until his retirement in 1998. During that time he concerned himself with teaching and research in particular in relation to problems of stylistics, semiotic, semantics and rhetoric. In his most important publications he has treated questions of stylistics, rhetoric, conversation as well as the didactical switching in linguistic questions.

Peter's publications, aside from those in Swedish, include 'On the place of stylistics' (1975), 'Linguistik, Stilistik und Pragmatik' (1977), 'Probleme der Beschreibung in der interpretativen Stilistik' (1977), and 'Regeln der alltäglichen Kommunikation als Grundlage der interpretativen Stilistik'(1981) - an essay on a well-known swedish short story by the Nobel prize laureat Pär Lagerkvist, based upon the rules of everyday conversation as construed by the philosopher H. P. Grice. In 1982 he published in English an investigation of political debate on Swedish television.

Peter Cassirer's research has thus been in the area of intersection between linguistics, stylistics and literature science. But most recently Peter has been working on an essay on Nobel laureat Imre Kertész's most well-known novel ('Fateless', Roman eines Schicksallosen) which he hopes will be published also in German.

Peter Cassirer has written a much cited paper reflecting as a grandchild on his grandfather Ernst Cassirer. The latest version of this paper can be viewed by clicking here.

London:

Manfred Cassirer (1920-2003)

For children ripped from their homeland and family, and plunged into an unfamiliar culture, the experience must have been particularly disturbing. Manfred Cassirer arrived in Paris af ter his mother, who was non-Jewish, had divorced his father under the racial laws and she married a Nazi. Manfred. who was thus half-Jewish, was sent to Paris to stay with an elderly female relative. Werner Falk went over to Paris from Oxford to fetch him. Manfred spoke no English and he was, not surprisingly, suffering from considerable psychological disturbance. Manfred stayed with Barbara and Werner Falk until he learned enough English to go to a Quaker tutor who specialised in emotionally disturbed children.

Manfred's father, Erich Cassirer, who had been first a philosopher, and then an art dealer (with a leading expertise in ancient Chinese art) also came to Oxford where he stayed for much of the war. Later he started a small gallery in London and after his death in 1963, Manfred inherited it. Barbara and Werner bought objects from Erich so he would have money to live on.

What happened to Manfred after that? Manfred eventually married an older women, Pauline Chenster. It is said that he he went to Oxford University where his subjects were theology and oriental studies and that he had a degree focused on Egyptology. Later in life Manfred Cassirer became extremely interested in seeking evidence of the paranormal. In the course of this research he wrote six books covering both psychical research and UFOs: He wrote six books on these subjects: Parapsychology and the UFO (1988), The Persecution of Mr Tony Elms: The Bromley Poltergeist (1993), Dimensions of Enchantment: The Mystery of UFO Abductions, Close Encounters and Aliens (1994), Medium on Trial: The Story of Helen Duncan and the Witchcraft Act (1997), The Hidden Powers of Nature (2001) and most recently Miracles of the Bible (2003).

One clue to Manfred's initial interest in this area is given in his book on the extraordinary prosecution of Helen Duncan, a self-styled medium, who was prosecuted in 1946 in the UK under the still surviving Witchcraft Act. Neither the Act nor Helen Duncan survived the events surrounding this trial and its aftermath. In his book Manfred Cassirer notes that Helen claimed that her husband's father Henry Duncan had made a pact with his son that whoever was to die first would seek to appear to the survivor. In the event a knock on the door, of the kind peculiar to Henry, is alleged by Helen Duncan to have occurred at the precise time of Henry's death. Manfred is appropriately reserved in his judgement of this uncorroborated and potentially self-serving account. Nevertheless he does note that the experience "is a common one" and "my own mother had it with her father". [Manfred Cassirer, The Story of Helen Duncan and the Witchcraft Act, PN Publishing, Essex, UK, 1996, p. 13]

Manfred Cassirer died alone in his London flat on December 18th or 19th 2003, aged 83.

West Chichester: Wilfred Cass (ne Wolfgang Cassirer)

Wilfred Cass, like his brother Eric, anglicised his name from Wolfgang Cassirer after his family came to England in 1933. There he learned a great deal from his pragmatic business like father Hans Cassirer who developed his commercial activity around the clothing trade. Wilfred became a very successful manager able to turn around large failing corporations. In the course of this very successful career he aquired both prominence and wealth. He and his wife Jeanette accumulated a significant sculpture collection and in 1990 moved to the Goodwood estate. With their collection accummulating they eventually decided to set up a sculpture park and toured Europe, America and Japan to find inspiration on how best to achieve it. The outcome is the Cass Sculpture Foundation established on the estate. The work is commissioned solely from British artists and all the pieces are ultimately sold with individual items remaining at the foundation for an average of three to four years. The Foundation is a not for profit organisation and all money raised is ploughed back into it. Since its inception, 120 works have passed through the park.

There is steady stream of press articles dealing with Wilfred's work and his foundation. For example, an article by Rupert Christiansen in the Spring 2005 edition of Bonhams Magazine notes:

Rolling over a West Sussex hillside, deep within the Goodwood estate a few miles north of Chichester, the Cass Sculpture Foundation extends across 26 wooded acres. Sixty-odd pieces are dotted among trees, lawns and ponds — some are monumentally grand, some austerely enigmatic, some smartly witty. Andy Goldsworthy has designed a sandstone arch that stretches like a rainbow over the estate's flint wall, built by French prisoners-of-war in 1790. Stephen Cox has perched ancient catamarans on rows of spindly granite pillars. At the end of a vista, Lynn Chadwick’s last work, an austere stainless-steel mobile, revolves in the wind. Tim Morgan’s Cypher is a huge translucent drum made up of glass rods, while Steven Gregory’s bronze shows a grinning fish surrealistically riding a bicycle. Wandering around this enchanted garden gives you a unique survey of the variety and invention that enlivens 21st century British sculpture.

It’s the creation of Wilfred Cass, a spry 80-year-old with a distinguished career in electronic engineering and management, who moved here with his elegant wife, Jeannette, in 1989, just after the devastations of the hurricane. The couple had a small personal collection — Henry Moore had been a friend — but the idea of reviving what had been a commercial forest by landscaping it as a sculpture park only came to them after they abandoned an initial plan for an open-air theatre. Nothing if not thorough, the Casses then spent a preliminary year visiting parks in Europe, North America and Japan, returning to Goodwood with a suitcase full of ideas, as well as bags of scepticism.

Recently, Cass was delighted to discover that a great-uncle “way back” had owned a sculpture park in Wilhelmine, in Germany, but his own father was a hard-nosed businessman who ran a paper-works and had “no interest in art whatsoever”. In 1942 Cass enlisted in the Royal Engineers, and after the war worked mostly in electronics, devising circuits for televisions. Later he had a huge success as a management consultant, sorting out companies as diverse as men's clothiers Moss Bros and art suppliers Reeves. Through his involvement with the latter, Cass came to know Henry Moore, who was interested in learning about watercolour, and it was this encounter that stimulated Cass' fascination with artistic creation.

|

|

Wilfred Cass |

Wilfred and Jeanette Cass [photograph - Cass Sculpture Foundation] |

South Africa: Reinhold Cassirer (1908-2001)

Reinhold Cassirer died in October 2001 after a long and spectacular life in South Africa. He was married to Nobel Prize laureate for literature, Nadine Gordimer, for fifty years. After serving in the South African army during the Second World War, he started a branch of Sotheby's auction house in South Africa which he ran for many years.

Reinhold Cassirer with his wife Nadine Gordimer |

Later picture of Reinhold Cassirer with Nadine Gordimer and Peter Cassirer (visiting) |

Nadine Gordimer has described her meeting with Reinhold, her introduction to his Berlin, and the subsequent work that she did with her film producer son Hugo Cassirer (who lives in the US). Click here to read Nadine Gordimer's account. A good account of Reinhold Cassirer's life and contribution is given in the South African Times below.

Sunday Times Obituary: Eccentric art dealer in a class of his own

Reinhold Cassirer, who has died in Johannesburg at the age of 93, was married to Nadine Gordimer for almost 50 years. Far from being overshadowed by the famous Nobel laureate for literature, his own contribution to the arts in South Africa was profound.

He established Sotheby's in South Africa in 1969 and ran it for 11 years before starting his own gallery, Cassirer's Fine Art, in Rosebank, Johannesburg. He identified, nurtured and exhibited some of South Africa's best artists long before they became famous. Major talents like William Kentridge, David Koloane, Sam Hlengethwa, Deborah Bell and Karel Nel were introduced to the world in his gallery.

When Kentridge lost all belief in himself as an artist and stopped painting, Cassirer - who was every bit as obtuse as he was enthusiastic - wouldn't hear of it. He cajoled and bullied the demoralised artist into picking up his brushes again.

Cassirer largely avoided being drawn into the fierce rivalry between dealers. When he retired he took Kentridge to lunch with Linda Goodman, founder of another famous Johannesburg gallery, and rather formally handed him over. This unusual gesture was as typical of the eccentric art dealer as was his parting admonishment to Kentridge to mind his table manners.

When exile Gerard Sekoto was down and out in Paris, Cassirer visited him there and decided to reintroduce him to the country of his birth. He mounted Sekoto's first one-man exhibition in South Africa, found buyers for his work and did more than anyone else to re-establish his name in SA.

Cassirer came from one of Germany's most intellectually, culturally and commercially distinguished families. He was born in Berlin on March 12 1908. His father, Hugo, who died when Reinhold was 12, was a leading industrialist who built up a successful cable manufacturing business and used his wealth to acquire a major art collection.

Reinhold's early life was steeped in the privilege that characterised the German elite of that era. He took a horse and cab to school, and hunting parties were de rigueur. He attended Heidelberg University and became a doctor of philosophy. He studied in Switzerland with his close friend Golo Mann, son of the writer Thomas Mann, and at the London School of Economics.

His life was turned upside down when Hitler came to power in 1933. Two years later the family business was confiscated by the Nazis, and later became part of Siemens. There was never any financial compensation, although there is today a Hugo Cassirer Street in Berlin.

Reinhold managed to save much of his father's art collection from the Nazis. He and a friend loaded the works onto a train and went to Holland. When confronted, they said the friend was an artist and they were going to exhibit his paintings in Amsterdam.

His uncle Bruno Cassirer is recognised as one of the most important art publishers of the 20th century. Another uncle, Ernst Cassirer, was a famous philosopher. When the cable manufacturing business was confiscated, a company agent in South Africa happened to be visiting and suggested the family emigrate there. While his uncle Bruno went to London and joined the publishing house Faber & Faber, and his brother Stefan went to Denmark, Reinhold came to Johannesburg, followed a couple of years later by his mother, Charlotte.

He joined the SA Army when World War 2 began, and was sent to Cairo, where he was seconded to British Intelligence with the rank of captain. He led a team that monitored all speeches and broadcasts from Germany. His father's business had supplied electrical equipment to mines around the world and, after the war, Cassirer used some of these connections to establish a mine engineering company. Art was always closest to his heart, however.

Refugees from Europe had brought a lot of valuable works with them to South Africa. Cassirer knew many of both the paintings and their owners. His family name had been highly respected in the art world of pre-war Germany, and he had an extensive knowledge of art. He was ideally placed to make the most of the opportunities that arose when they decided to sell. When the then chairman of Sotheby's in London, Peter Wilson, visited South Africa in 1969, Cassirer persuaded him to open a branch of the auction house in South Africa, and let him run it.

Cassirer brought a novel integrity and aesthetic standard to the art business locally. He abhorred some of the practices he observed. Passing something off as a Rembrandt, for example, without authentication, was something he would never have dreamed of doing. No more did he keep quiet about a work which he knew had been heavily restored. It was not altogether surprising that, by the time he retired from Sotheby's in 1980, he'd put most of the once leading auctioneers in town out of business. The respect he commanded overseas helped him open up the SA art market to the world. In the mid-1970s he persuaded Sotheby's to hold sales of Impressionist artists in South Africa for two or three years, and it is thanks to him that many South Africans are the proud owners of paintings that would certainly be beyond their means to buy today.

As a dealer Cassirer was unusually frank about the quality of work presented to him, often to the point of being found abrasive. But there was no arrogance about him, and artists soon learned to respect his honesty. In 1954 Cassirer became Gordimer's second husband, and she his third wife. He is survived by three children.

Chris Barron Sunday Times Location: Sunday 28 Oct 2001 Insight , Sunday.Times.Co.ZA

More on Reinhold Cassirer's childhood, formative years, life, and insights is given in and interview he gave in 1986. To view this interview click here.

Sophie Cassirer (~1901 - 1979)

There is much more to be told than what is recounted above. The scattering was not only across the world, but also the knowledge is held in scattered memories. For example, when this was first written the author had no knowledge of the fate of Sophie Cassirer, daughter of Bruno Cassirer. A poignant reminder of her could be found in the image, still existing in the portrait below of her (and discovered on the Web), as a child, painted in 1906 by Lovis Corinth.

But more is available in the family memories if only it can be compiled together. On the initial publication of this site one relative, Peter Cassirer, sent generously provided a copy of a book presented on 4 September 1989 to him by Reinhold Cassirer. The book "Bruno Cassirer", by Harry Nutt (Stapp Verlag, Berlin, 1989) contains much of interest including a paragraph

Sophie heiratet den Altphilologen Richard Walzer, der in der Festschrift Vom Beruf des Verlegers über seinen Schwiegervater sagt: "Im echten Manne ist ein Kind versteckt - die Kraft der Jugend, sich allem Neuen immer wieder zu öffnen, als hätte man ein langes Leben voll echter und ernster Erfahrung hinter sich, spüren wir Jüngeren zugleich aber auch die Festigkeit und klare Besonnenheit des Mannes, dessen Wurzeln in glücklichere und gesichertere Zeiten zurückreichen." Sophie und Richard gehen 1938 ebenfalls nach Oxford und bleiben dort bis zu ihrem Tod in den 70er Jahren.

So now we know that Sophie married Richard Walzer and, after they fled from Germany, reached Oxford along with other Cassirers where Sophie and Richard died, some time in the 1970s. (Her sister Agnes died in Oxford sometime in the 1950s.) But it turns out that more can pieced together from the scattered references on the global 'information superhighway'.

For example, further information on Sophie can be found in the records of the Philadelphia Museum in the US, where the above painting now resides. Its notes as to provenance reveal that the painting was purchased by Bruno Cassirer but was confiscated by the Nazi authorities in 1938 and purchased by the Nationalgalerie, Berlin, on March 16, 1944. Later (probably between 1960-1962) it was restituted to Sophie Cassirer as Bruno's heir (in stark contrast to the treament of Claude Cassirer's Pissarro). The notes show Sophie died in 1979 in Oxford. The painting was sold to the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1975.

A further article by one Martin Kramer describes the work of Sophie's husband Richard Walzer, who it appears, made an interesting intellectual contribution to Islamic studies:

Or perhaps a point of departure might be Richard Walzer (1900-75) born in Berlin, who specialized in Islamic philosophy, and who sought the continuity of Greek tradition in the Islamic world, demonstrated by the preservation of lost Greek materials in Arabic philosophical texts. In 1933 he left Nazi Germany for the University of Rome, and then in 1938 relocated again to Oxford. Albert Hourani has attested to Walzer's influence there: 'He and his wife Sofie had a kind of salon in which, among Biedermeier furniture and with the lovely Monet inherited from her parents looking down at us from the wall, we would meet colleagues and visiting scholars, and where books were discussed and a kind of stock exchange of scholarly reputations was held. Richard taught me the importance of scholarly traditions: the way in which scholarship was passed from one generation to another by a kind of apostolic succession, a chain of witnesses (a silsila, to give it its Arabic name). He also told me much about the central tradition of Islamic scholarship in Europe, that expressed in German.'

Further references to Richard Walzer's work can be found in the American Journal of Islamic Studies (Winter 2002).

A final intriguing glimpse of the life of Sophie and Richard in Oxford is drawn from the following excerpt from the Ashmolean Museum's Report 1999/2000 headlined Cézanne Theft.:

In the early hours of 1 January, Paul Cézanne's Auvers-sur-Oise was stolen from the Hindley Smith Gallery. This was a terrible loss to the Ashmolean. This criminal act removed a great painting—the Ashmolean's only painting by Cézanne—from a public institution where it can be seen free by our many visitors. It was particularly cruel in that the painting—along with other outstanding twentieth-century paintings and drawings—was presented to the Ashmolean by Richard and Sophie Walzer, who had sought refuge from Hitler's Germany in Oxford. With this gift they wished to record their gratitude to this country and to Oxford in particular.

The above tells us something not only about Sophie Cassirer, but also the extent to which the family history has been dispersed, the efforts needed to seam the memories back together, and the healing potential of dispersed relatives and others around the world interacting with the developing global information systems to assist in making this happen. Clearly, there are many other memories to be assembled, and more work to be done.

The above are just a few examples where information can be easily found on the public record. One reminder of the continuing connection of living descendants to the singular events that scattered the Cassirers across the world can be found in the reports of the US Claims Resolution Tribunal . This was established in 1997 to arbitrate claims to 5,570 dormant accounts in Swiss banks. Following a complex process $1.25 billion was placed in a fund to settle claims by five groups of victims of the Holocaust: the "Deposited Assets Class", the "Looted Assets Class", the "Refugee Class", and two "Slave Labor Classes". In December 2004 the CRT made judgements in favour of living relatives of Bruno and Ernst Cassirer. Interestingly the CRT has one footnote to its judgements: it is to this website. The CRT apparently visited here in October 2004 as part of its research of the claims. The judgements can be seen by clicking here.

A glance at the family tree will show a large number of related families which have grown up across the world, springing from the Cassirers scattered by the events referred to above. Those events may have left severe marks on that generation and all who shared their experiences. It is also true to say that subsequent generations may also have gone about their business largely unscathed. But even the information in the family tree shows the way in which some of the Cassirer heritage appears to have stuck, either in how they developed or who they chose as their partners. There is an extraordinary preponderance of professionals, with what may be a surprising number entering intellectual professions, including many academics. There is also a tendency for those who have been identified to continue to express values of concern about insult to human rights, or the environment.

There are of course many people related to the Cassirers who will have been overlooked. They are those who do not feature in the media, whether electronic or print, and who have not been identified in the genealogical searches undertaken by people like Michael Geballe.

The Berlin Reunion in 2002 may give some additional insight into the lives of those who are interested to continue to identify themselves, at least in part, through their descent from the Cassirer family. Perhaps there are more descendants for whom this is a matter of at least passing interest and who feel they would like to get this part of their history into more coherent perspective. If so, whether it is to correct misimpressions given here, or to add additional interpretation, analysis, stories or biographical sketches, your input, by clicking on genealogyprotected@ meta-studies.net will be very welcome.

Jim Falk

Back to Overviews First Page / Return to Home Page

Cassirer: Schwientochlowitz to Breslau; Breslau to Berlin; Music, Publishing and Art; Continuing the Entrepeneurship; Daughters